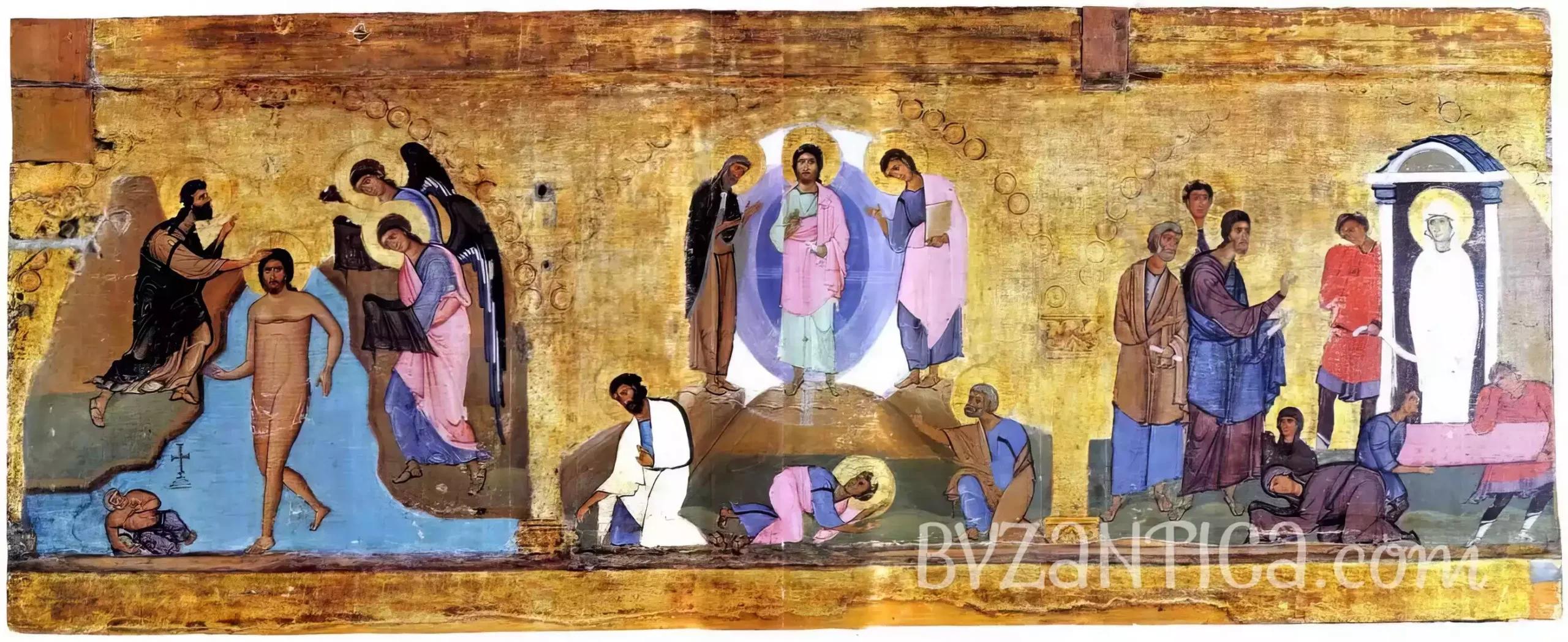

Title: The Baptism, Transfiguration, and Raising of Lazarus

Artist Name: Unknown Byzantine Master

Genre: Religious Narrative Art

Date: First Half of 12th Century AD

Materials: Tempera and gold leaf on wood

Location: Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai, Egypt

Between the Earthly and the Divine

In the sacred environment of the Monastery of Saint Catherine of Sinai, in Egypt, is preserved one of the most significant examples of Byzantine ecclesiastical art of the 12th century. The epistyle beam of the templon, which bears scenes from the Dodekaorton, constitutes a work of an unknown Byzantine artist, executed with tempera and gold leaf on wood during the first half of the 12th century A.D. The work presents three central moments from the earthly ministry of Christ: the Baptism, the Transfiguration and the Raising of Lazarus.

The golden surface of the work, which functions as a background for the three narrative scenes, transforms the material wood into a sacred space. This technical choice does not simply constitute a decorative element, but a theological statement that unites the visible with the invisible. The soft blues, the pinks and the rich purple colours create a visual harmony that guides the gaze through the narrative sequence.

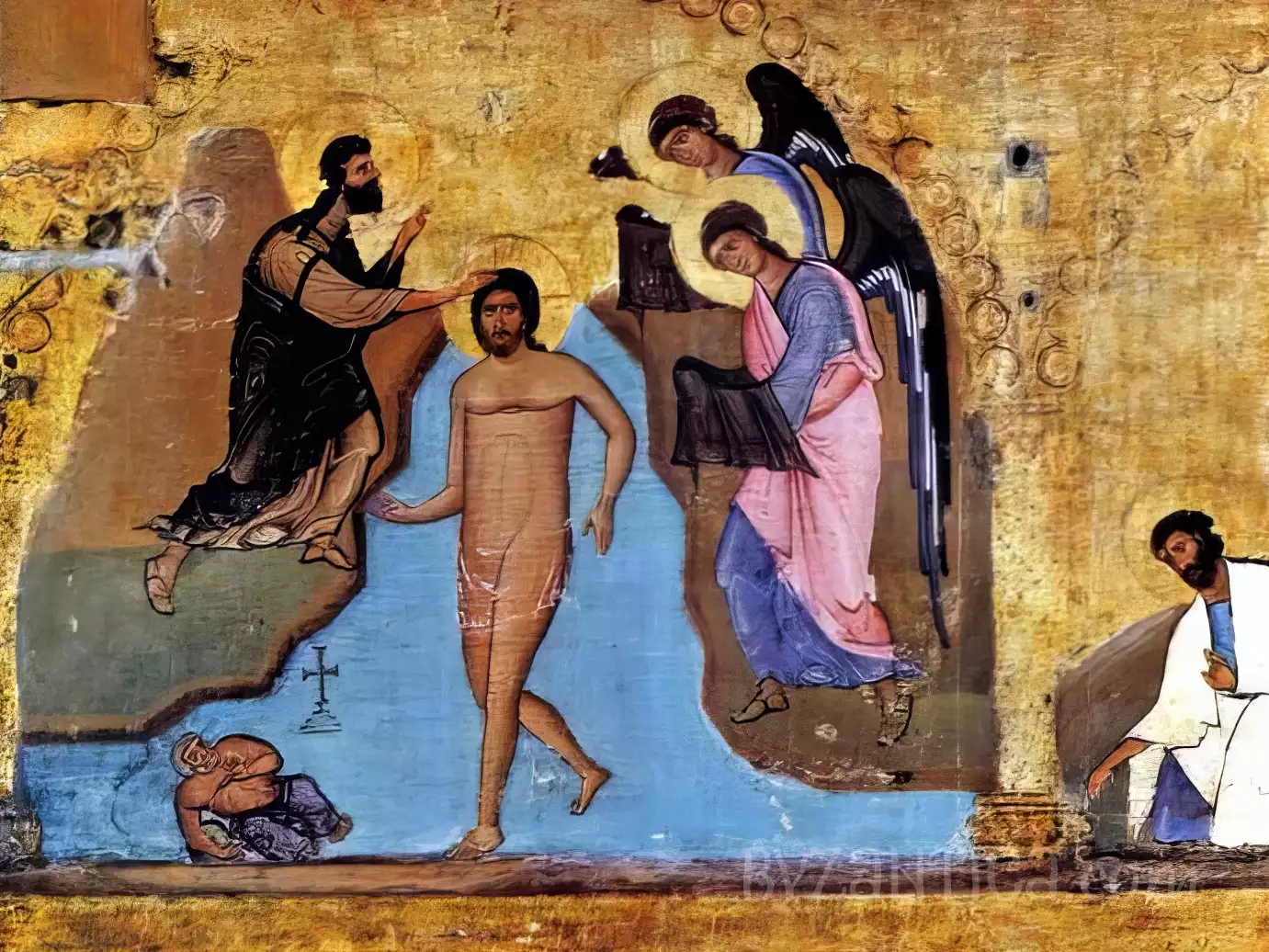

The Baptism: The Encounter of the Human with the Divine

The first scene captures the moment of the baptism of Christ in the Jordan river. Christ stands in the waters, his body slightly bent in humble submission, while the figure of John the Baptist leans forward from the rocky bank. Two angels await in a stance that suggests simultaneously reverence and ministry. The artist has captured that precise moment where the heavens open to the earth — the moment of divine recognition.

Every movement of the brush serves the sacred narrative. The paint has been applied with exceptional sensitivity, creating subtle gradations in the tones of the flesh and the vestments. This technical excellence suggests an artist of significant skill, possibly working in some important centre of Byzantine artistic production. As Helen C. Evans mentions in her study on the Monastery of Saint Catherine, ‘the collection bears witness to the continuous tradition of Byzantine art’.

The gold background unifies the three scenes while simultaneously it separates them from the earthly reality. The result would have been even more impressive in its original environment, where the flickering light of the oil lamps would have made the gold appear alive with motion.

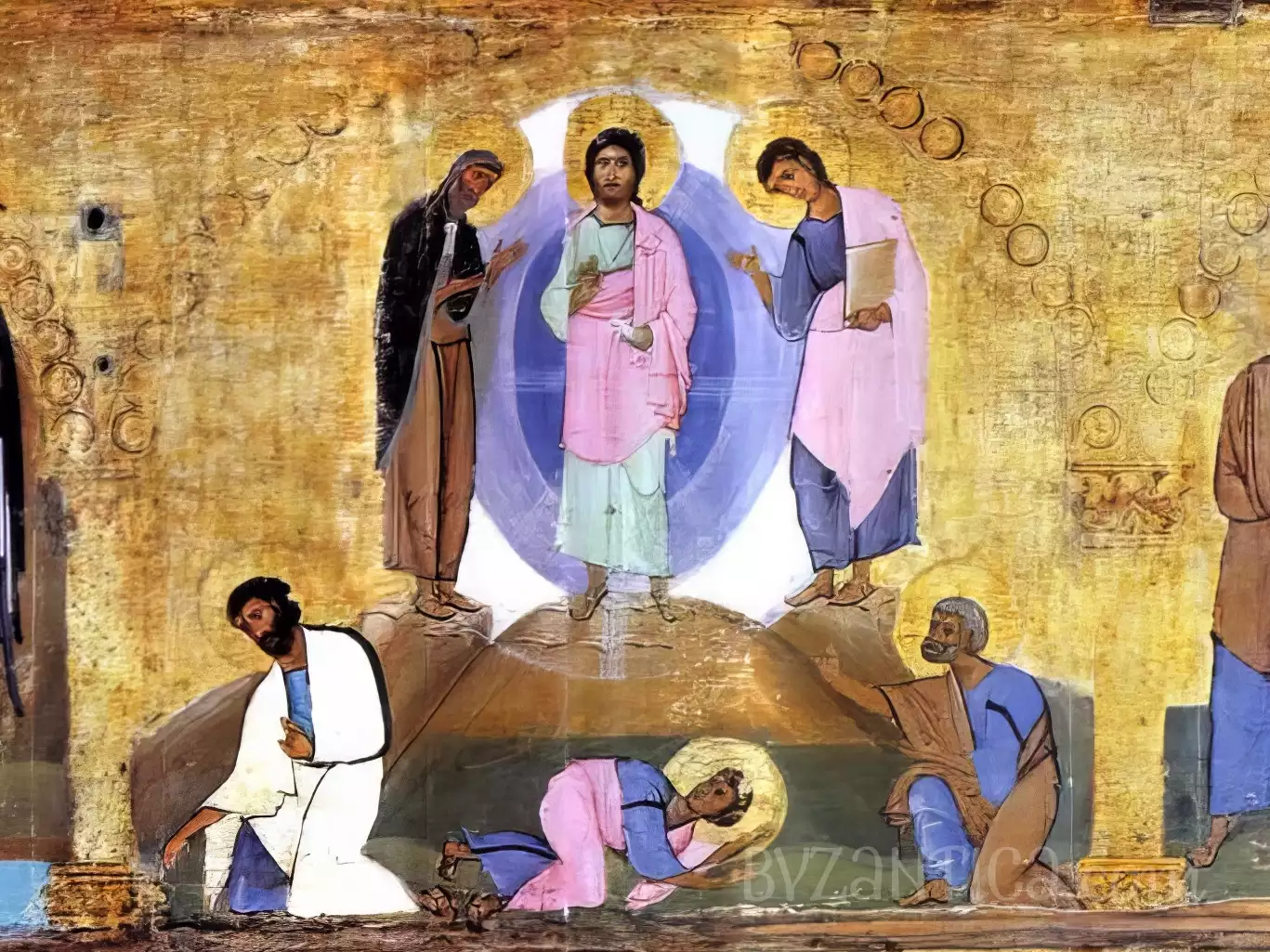

The Transfiguration: Vision of Light and Glory

The central scene of the Transfiguration is elevated like a brilliant vision against its golden field. Christ stands transfigured on the peak of Mount Tabor, his vestments a soft pink that seems to capture and to hold the light. The composition leads the eye upwards through a careful placement of the figures — the disciples below, Christ raised above, all united by the brilliant radiance of the mandorla.

Within this scene the artist demonstrates his ability to capture not only the physical presence but also the spiritual transformation. The arrangement of the colours — from the earthy browns and blues of the disciples to the otherworldly pink of Christ — creates a visual hierarchy that reflects the theological teaching about the nature of Christ. As Andrew Paterson notes in his study on early Christian icons, ‘the iconography of the Transfiguration expresses the union of human and divine’.

Perhaps the most noteworthy element of this scene is the way in which the light becomes substance. It is not a matter of symbolic representation but of a visual reality that is created through the technique. The use of gold and of the light tones transforms the surface of the wood into a source of light.

The Raising of Lazarus: Drama of Life and Death

The final scene presents the Raising of Lazarus with astounding theatrical intensity. The figures gather around the entrance of the tomb: Christ commands with a raised hand; Mary and Martha kneel in prayer; Lazarus appears covered in burial shrouds. The artist has captured the interface between death and rebirth.

The dark shadows in the opening of the tomb are contrasted with the brilliant figures, thus emphasising the power of the miracle. This visual contrast is not accidental — it constitutes a conscious theological choice that highlights the opposition of light and darkness, of life and death.

The technical execution reveals an artist who understands deeply not only the iconographic traditions but also the psychological dimensions of the narrative. Each figure bears its own emotional charge — from the command of divine authority in the figure of Christ to the human sorrow and hope in the women.

Theological Significance and Liturgical Role

This epistyle beam did not function merely as a decorative element but as a theological text written with colours and light. As Judith Couchman emphasises in her study on Christian images, ‘the Transfiguration reveals the glory of God’. Its placement on the templon created a sacred boundary between the clergy and the laity, between the earthly and the celestial.

The selection of these three scenes is not accidental. They represent three central moments of revelation in the earthly ministry of Christ: the recognition of his divine nature (Baptism), the manifestation of his glory (Transfiguration) and the demonstration of his authority over death (Raising of Lazarus). Together they form a theological trilogy that prepares the faithful for the understanding of the mystery of the incarnation.

Technical Analysis and Artistic Value

The examination of the technical execution reveals an artist with a profound understanding of both the Byzantine tradition and the modern developments of the 12th century. The movements of the brush are confident and detailed, particularly in the renderings of the faces and the hands. The use of tempera permits subtle gradations of colour that create a sense of depth and volume.

The gold background, besides its theological significance, also serves aesthetic purposes. It creates a unified surface that joins the three separate scenes into a single narrative whole. Simultaneously, the reflection of the light on the gold would have given the work a dynamic quality, making it appear different depending on the time of day and the intensity of the illumination.

Historical Context and Cultural Significance

The Monastery of Saint Catherine of Sinai constituted during the 12th century a significant centre of monastic life and artistic creation. As Marc Cels notes, ‘Saint Catherine’s Monastery was built between 527 and 565 by the Roman ruler Justinian’. Its remote location protected it from the iconoclastic controversies and allowed the preservation of a significant number of Byzantine works of art.

This epistyle represents a period of recovery for Byzantine art after the end of iconoclasm. The artist combines the traditional Byzantine iconography with modern elements that testify to the renewal and the evolution of the style during the 12th century.

In the atmosphere of the sanctuary, where the candle and the incense create a sensory experience of total religious devotion, this work would have functioned as a window towards the divine. The faithful, as they approached the holy bema, would have beheld these scenes and would have been moved to contemplation on the mysteries of the faith.

The preservation of the work to this day constitutes a testimony not only of its artistic value but also of its spiritual significance for the monastic community that guarded it for nine centuries. Each generation of monks that passed before it saw the same image of divine revelation, thus participating in an uninterrupted tradition of worship and contemplation.

Bibliography

- Cels, Marc. Life in a Medieval Monastery. London: Cavendish Square Publishing, 2005. https://books.google.com/books?id=K6I9FvJZGzUC

- Couchman, Judith. The Mystery of the Cross: Bringing Ancient Christian Images. Colorado Springs: NavPress, 2010. https://books.google.com/books?id=x2EKt2ZfDWwC

- Evans, Helen C. Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai, Egypt: A Photographic Essay. New York: Princeton University Press, 2004. https://books.google.com/books?id=izr8rGsQ0UoC

- Forest, Jim. Praying with Icons, Third Revised Edition. Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 2025. https://books.google.com/books?id=5d1MEQAAQBAJ

- Paterson, Andrew. Late Antique Portraits and Early Christian Icons: The Power. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022. https://books.google.com/books?id=YzlvEAAAQBAJ