Title: Christ Pantocrator

Artist Name: Theophanes the Greek

Genre: Icon

Date: 14th century AD

Materials: Egg tempera and gold leaf on wood panel

Location: Holy Monastery of Iviron, Mount Athos

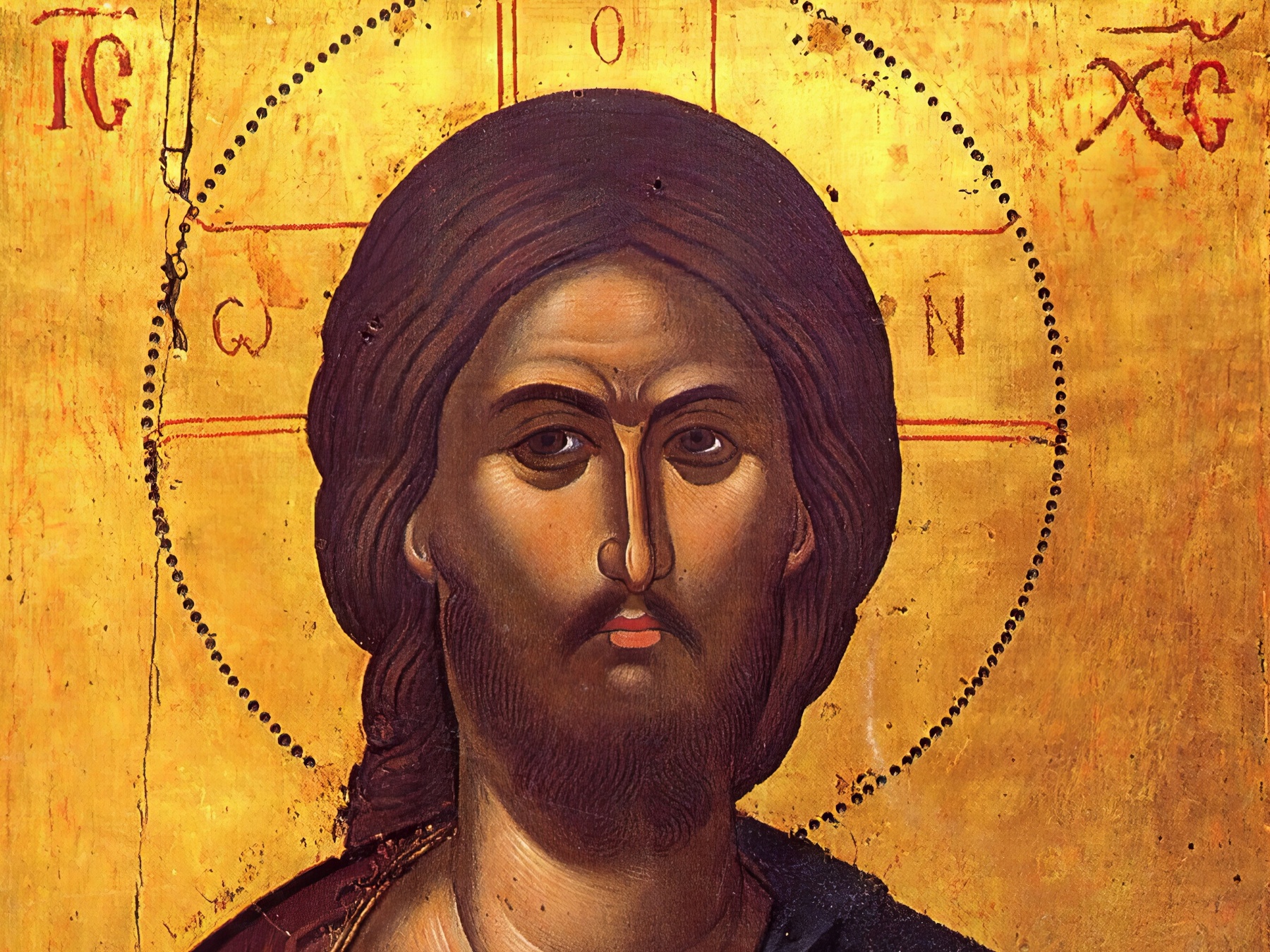

There are works that transcend simple aesthetic pleasure; they function as spiritual axes, points of intersection where time meets eternity. The icon of Christ Pantocrator, a work attributed to the great Theophanes the Greek and dated to the 14th century, is such a case. Kept in the Holy Monastery of Iveron on Mount Athos, this portable icon, crafted with the traditional technique of egg tempera and gold leaf on wood, is not merely a depiction; it is a theological treatise that unfolds silently, an invitation to a dialogue with the very mystery of the Incarnation.

The first contact with it—even through the distance that reproduction imposes—leaves a sense of awe, an almost tangible presence that seems to rearrange the space around it. Here, the artist does not seek merely to represent, but to make present. The gaze is fixed, almost involuntarily, upon a face that contains an inconceivable intensity, an antinomy that constitutes the core of the Christian faith: the austerity of the Judge coexists with the infinite compassion of the Redeemer. How can a single face, constructed with colour and light, bear the weight of such a dual nature? And how does matter—the wood, the pigments, the gold—become the vehicle for the revelation of the absolutely immaterial? It is precisely here, on the threshold of these questions, that our investigation begins.

The Structure of the Face: Between Divine Justice and Human Condescension

Theophanes’ technique, deeply rooted in the hesychastic tradition, is not just a medium, but part of the theological message itself. The face of Christ is not shaped according to the terms of a naturalistic illusion. It is structured, on the contrary, through a strict geometry of light and shadow, a process that could be paralleled with spiritual exercise itself. The dark underpaintings, the earthy tones of the base, perhaps symbolise the earth of the earthy (Gr. χοῦν οἱ χοϊκοί), the human nature that the Word assumes; upon this dark substrate, the lights are spread gradually, in thin, almost ethereal layers, as if the divine nature permeates and transforms the human, without, however, abolishing it.

And then, the eyes. It is they that constitute the centre of gravity of the entire composition. Asymmetrical to each other—a detail often found in the iconography of the Pantocrator and denoting the dual nature, the divine and the human—they look simultaneously in two directions: towards the world, with the penetrating gaze of the all-seeing Lord, and towards the inner world of the faithful, with a silent invitation to repentance. The one eye, slightly larger and more open, seems to emit incorruptible justice; the other, more contracted, almost melancholic, expresses condescension and love. This is not a simple psychological observation; it is the visual rendering of dogma. As Mary E. Green observes, “The word Pantocrator is often translated as ‘Almighty,’ but it also contains the meaning of one who governs and sustains all things”, an idea that Theophanes conveys not with symbols of power, but with the very internal structure of the gaze.

The form is not static. An imperceptible movement runs through everything. The hair, rich and wavy, falls upon the shoulders with a naturalness that breaks the frontal austerity, while the line of the forehead, high and broad, emphasises wisdom and spiritual authority. The mouth, closed, with its corners turned slightly downwards, maintains the silence of the holy, a silence that is not an absence of speech, but its transcendence. It is the silence from which the Word Himself springs, through whom all things were made (John 1:3). Every feature of the face, every line, seems to be the result of a profound meditation on the relationship between the created and the uncreated, the visible and the invisible.

The Golden Ground and the Book of Life

If the face is the theological core of the icon, the surrounding space functions as the frame that defines and highlights its meaning. The golden depth, the “kampos” (ground), is not merely a decorative background; in Byzantine aesthetics, gold does not symbolise material wealth, but the divine light itself—a light uncreated, eternal, which does not originate from any earthly source. It functions as a metaphysical space, which negates the perspective of the three-dimensional world and places the figure of Christ in a dimension beyond time and place. One could imagine this icon in its original setting, in some chapel of the monastery, bathed in the uncertain light of candles, and see the flames making the surface of the gold vibrate, come alive, creating a sense that the divine presence is not merely depicted, but active and dynamic. This dialectic of light and material transforms the icon from an object of observation into a place of encounter.

The hand that blesses, with the fingers formed in the typical arrangement that signifies the name “IC XC”, is not a static gesture, but an act in progress. The blessing flows from the icon towards the viewer, making him a participant in the economy of salvation, a movement that bridges the distance and lifts the isolation of the faithful. In his left hand, Christ holds the Gospel, heavy and lavishly decorated with stones that capture the light. That it is closed has multiple interpretations: on the one hand, it symbolises the word of God that has already been revealed, complete and self-sufficient; on the other, it suggests that its full understanding belongs only to the Word Himself, while for man the revelation remains partly a mystery. It is the book of life, where the names of the righteous are written, but also the Law by which the world will be judged, because, as the Apostle Paul also states, “For the word of God is alive and active, and sharper than any double-edged sword” (Hebrews 4:12).

The Garment of the Incorruptible Body

The vesture, with its rich drapery, completes the theological composition. The dark blue mantle (the himation) that covers the crimson chiton follows a long iconographic tradition, where blue, the colour of transcendence and of heaven, symbolises the divine nature that envelops the human, which in turn is symbolised by the crimson—the colour of blood and of royal authority. The folds do not obey a strictly realistic logic, but create a dynamic, almost abstract play of lines, while the gold striations that run through the fabric suggest the rays of divine glory emanating from the body of Christ, transforming everything. The elaborate frame of mother-of-pearl, with its geometric motifs, acts as the boundary between our own, corruptible world and the incorruptible, eternal world of the icon. M. Shane Bjornlie, referring to similar icons, stresses the importance of portability, which makes the icon a personal, almost intimate, place of encounter with the divine, a microcosm that can transform any space into a place of prayer: An icon, a painting on a board, differs from a painting on a wall in that the former is portable.

The Gaze that Remains

Ultimately, what is it that makes the Pantocrator of Theophanes a work that endures through time, not merely as an artistic masterpiece, but as a living spiritual presence? The answer, perhaps, lies precisely in this balance of opposites, in this masterful fusion of dogma and art, of the human and the divine. Theophanes does not simply paint an idea, but he incarnates it, inviting us to stand before a face that knows us completely—“You shall not put the Lord your God to the test” (Luke 4:12) could be its silent warning—but which simultaneously offers us the path of salvation. This icon is a constant reminder that at the heart of Orthodox spirituality, dogma is not an abstract philosophical proposition, but a lived reality, a reality that can become visible, can almost be touched, through sanctified matter. The Pantocrator of Theophanes remains, centuries after its creation, an open window towards the mystery, a gaze that continues to call us to a dialogue beyond words.

Bibliography

- The Life and Legacy of Constantine: Traditions through the Ageshttps://books.google.com/books?id=aIyuDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA141&dq=Christ+Pantocrator&hl=el&newbks=1&newbks_redir=1&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiGo8rM16iOAxWHFlkFHdNjO9A4KBDoAXoECAwQAw

- Geffert, B., and T. G. Stavrou, Eastern Orthodox Christianity: The Essential Texts (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), https://books.google.com/books?id=YVKODQAAQBAJ&pg=PR14&dq=Christ+Pantocrator&hl=el&newbks=1&newbks_redir=1&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiGo8rM16iOAxWHFlkFHdNjO9A4KBDoAXoECAYQAw

- Green, M. E., Eyes to See: The Redemptive Purpose of Icons (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2014), https://books.google.com/books?id=g9CRBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA77&dq=Christ+Pantocrator&hl=el&newbks=1&newbks_redir=1&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiT-KDk16iOAxXIGFkFHUSxJ8g4FBDoAXoECAYQAw