Title: The Baptism, Pentecost and Dormition of the Virgin Tetraptych Panel

Artist Name: Unknown Master of Sinai

Genre: Religious Icon

Date: Second Half of 12th Century AD

Materials: Egg tempera and gold leaf on wood panel

Location: Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai, Egypt

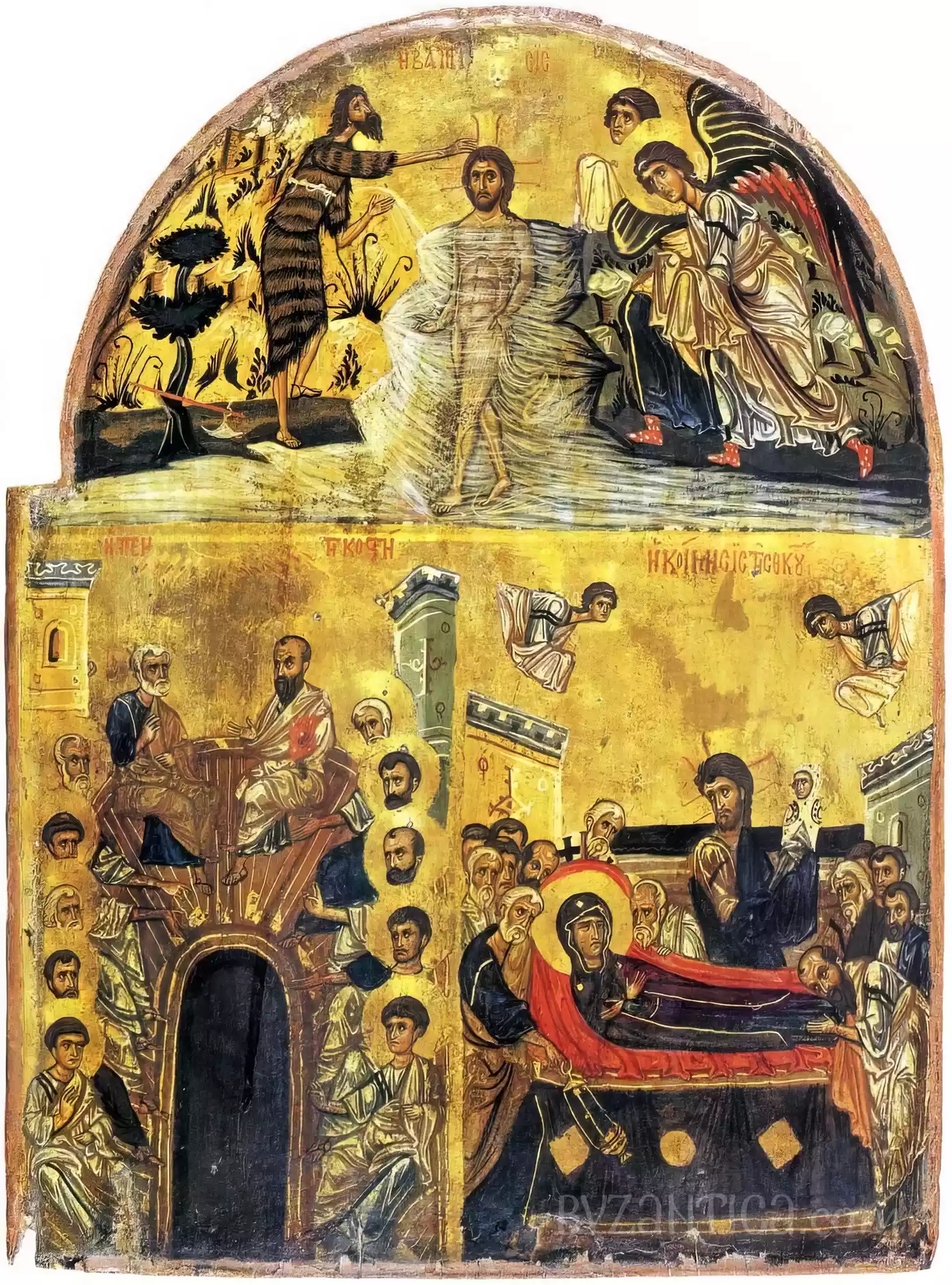

Before the tetraptych of the Dodekaorton from the Holy Monastery of Saint Catherine at Sinai, a work most likely created during the second half of the 12th century, the viewer does not simply stand before a religious icon; he enters an intellectual temple made of colour, light, and theology. This work, painted with the technique of egg tempera and gold leaf on a wooden panel, with dimensions that permit internal self-concentration but also collective worship, was not constructed for depiction, but for transcendence (Walters Art Gallery et al.). The approach to such a work as a historical object, stripped of its functional immediacy, requires a shift in interpretive focus—a shift from simple religious piety to historical and morphological analysis—because only thus is its elaborate compositional logic revealed, the internal architecture of meaning that renders it a cultural testament of incalculable value.

It was not a first contact with art. But there, before this composition, something different occurred; as if I found myself again in a space I already inhabited. The gold, which elsewhere would function as a symbol of luxury, here does not decorate; it diffuses a divine energy, defining not a place, but a way of seeing. The contact was not with the icon, but with its time; with eternity. Here, the object ceases to be merely a vehicle of faith and is transformed into a text, into a palimpsest of materials, techniques, and theological intentions that invite the analyst to decode their language, a language where every brushstroke is a syllable in a narrative that transcends historical time, while simultaneously being absolutely founded within it.

Holy Geometry and Ontological Structure

The structure of the tetraptych is not a random arrangement of scenes, but a strictly hierarchised cosmology. The composition of the work’s upper and lower zones does not obey rules of aesthetic symmetry, but an internal, theological geometry that defines the relationships between the figures and the events. The upper zone of the work is not “upper” only spatially; it is theologically oriented towards the heavens. The Baptism of Christ occupies the summit as an iconographic culmination, isolated not in distance, but in density of presence. Here geometry becomes revelatory; the symmetry is asymmetrical, and yet balanced.

John, with his raised hand and his garment of hair, stands in solid counterpoint to the angels, who, clustered together, convey not merely form but a movement of reverence. The body of Christ, at the centre of the axis that permeates the panel, is not simply an anatomical form but the theological centre of gravity of the entire composition. His nakedness is not naturalistic; it is ontological, signifying the human nature assumed by the divine. The austerity of the scene culminates in a semantic fullness. The gold background, which would normally serve perspective, here creates a conceptual transparency. The gold does not “build” depth, but establishes eternity. The icon does not imitate an event; it repeats it, transformed into an ontological type, accessible not to historical memory, but to liturgical viewing.

The Materiality of Transcendence: Technique and Light

The analysis of the technique of the unknown Master of Sinai reveals that the materiality of the work is not merely the medium, but part of the message itself. Christ’s garments in the Baptism scene are illuminated from within. The white does not reflect the light; it produces it. The use of white, linear brushstrokes for the drapery is not realistic but mystagogical. Each fold does not merely denote a body, but a nature—the divine humanity. The light does not fall upon the figures from an external source, as would happen in western painting, but springs forth from them, transforming the figures into bearers of an inner, uncreated effulgence.

The technical skill unfolds gradually, through a process of successive layers. Subterranean hues of a red underlayer emerge beneath the cool shadows, bestowing upon the light not just warmth, but memory. We are not dealing with “shadow” in the naturalistic sense, but with theological withdrawal, with a form of visual stillness that allows the light to be revealed with greater intensity. As Mango observes, Byzantine art often uses the material to suggest the immaterial, and in this tetraptych this principle finds its absolute application (Mango). The cool blue shadow of the robes is combined with golden highlights that suggest not naturalness, but the advent of the Divine. The wood itself, as a material, bears the weight of history, while the egg tempera, with its transparency, allows the layers of colour to interpenetrate, creating a visual effect that is simultaneously dense and ethereal. Art here does not represent, but transubstantiates matter into spirit.

The Architecture of Meaning and the Theological Synopsis

Descending to the lower zone, the gaze does not lose in significance; it is defined by architectural forms that substitute perspective with symbols. The scenes of Pentecost and the Dormition of the Theotokos are multiple, not isolated but continuous, like musical phrases that complement each other. The edifices do not serve depth, but meaning; they are theological verbs that frame and interpret the action. In the Dormition of the Theotokos, the scene condenses an entire theological treatise. The Theotokos is asleep, but not as a mortal; her state resembles an initiation. The serenity on her face transcends death; it renders it a mystery.

The Apostles move, prostrate themselves, pray, but the scene remains motionless, frozen in a moment of eternal significance. The artist, being aware of the danger of overloading, restrains the expressiveness within limits of austere emotion, avoiding theatrical melodrama. The architectural frames create interiority; each arch and roof is not a background, but a frame for a theophany, a demarcated space where the human meets the divine. This use of architecture as a semantic tool, and not as a simple decorative element, is characteristic of mature Byzantine art, which seeks to organise the space of the icon according to a spiritual and not a physical logic, an approach that we find in many works of the period. Every column, every lintel, becomes a point of punctuation in the visual narrative, guiding the viewer in the reading of the multiple levels of meaning.

The Gaze as an Interpretive Tool and the Metaphysical Perspectiv

In the lower right scene, a gateway—dark, deep, geometrically precise—functions as a visual magnet, drawing the observer’s gaze. Here “perspective” does not function as in western painting; it does not terminate at a vanishing point, but opens inwards. It is the gateway not to space, but to meaning. The Apostles do not pass through it; they guard it with their gaze, making it a boundary between the visible and the invisible, the historical and the eschatological. The artist has used the bodies not as forms, but as scales; every movement raises or lowers the gaze, every stance defines an axis of viewing.

The gaze of the Apostles is not merely a psychological expression; it is an interpretive tool that the painter provides to the viewer. Through their eyes, we are invited to see not only the scene, but also its significance. Their gazes converge, diverge, intersect, creating an invisible grid of lines that structures the conceptual space of the icon. This management of the gaze transforms passive viewing into active reading. The viewer does not merely observe, but participates in a visual liturgy, following the indications of the figures to penetrate the deeper layers of meaning. It is a process where the human eye learns to see in a theological way, transcending the surface of the colour to touch the essence of the mystery.

The Icon as a Historical Palimpsest

The analysis of the tetraptych of the Dodekaorton as a historical object does not strip it of its spiritual power; on the contrary, it reveals it in all its complexity. This work is a palimpsest, where upon the material base of wood and colour have been inscribed layers of theology, cultural conventions, and artistic intention. Every element, from the choice of the gold background to the last line of the drapery, is a carrier of a meaning that transcends simple representation. The unknown Master of Sinai did not merely paint scenes from the life of Christ and the Theotokos; he composed a visual theological system, a world where space, time, and matter obey other laws.

This icon, as a historical testament, bears witness to a civilisation that perceived art not as decoration or mimesis, but as a form of knowledge, as a window towards another reality. To stand before it with an analytical gaze is, ultimately, to recognise that the transcendence is found not only in the subject, but also in the method; in the dialogue between light and shadow, line and colour, visible and invisible. The tetraptych is not just an object of history; it is an object that produces a consciousness of the trans-historical, transforming the viewer from a simple observer into a participant in a continuous revelation. And in this transformation, in this alchemy of the gaze, lies its timeless power and its indestructible cultural value.

Bibliography

- Blišák, Ľubomír, ‘Volunteer Project to Preserve the Cultural Monument of Church and Monastery of Saint Catherine’, European Journal of Science and Theology, vol. 12, no. 6, 2016, pp. 233–243, http://www.ejst.tuiasi.ro/Files/56/24_Blisak.pdf.

- Evans, Helen C., Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai, Egypt: A Photographic Essay (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004), https://books.google.gr/books?hl=el&lr=&id=izr8rGsQ0UoC&oi=fnd&pg=PA11.

- Mango, Cyril A., The Art of the Byzantine Empire 312–1453: Sources and Documents (Toronto: Medieval Academy of America, 1986), https://books.google.com/books?id=rSvf_KMYQiwC&printsec=frontcover.

- Parani, Maria G., ‘Byzantine Cutlery: An Overview’, Δελτίον της Χριστιανικής Αρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας, vol. 31, 2010, https://ejournals.epublishing.ekt.gr/index.php/deltion/article/view/4407.

- Walters Art Gallery (Baltimore, Md.) et al., Early Christian and Byzantine Art: An Exhibition Held at the Brooklyn Museum (Baltimore: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1947), https://books.google.gr/books?id=QlgvAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA133.