Tetraptych Dodekaorton from Sinai

Title: The Annunciation, Transfiguration, and Raising of Lazarus Tetraptych

Artist Name: Unknown Byzantine Master

Genre: Religious Icon Painting

Date: Late 12th century AD

Materials: Tempera and gold leaf on wood

Location: Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Mount Sinai, Egypt

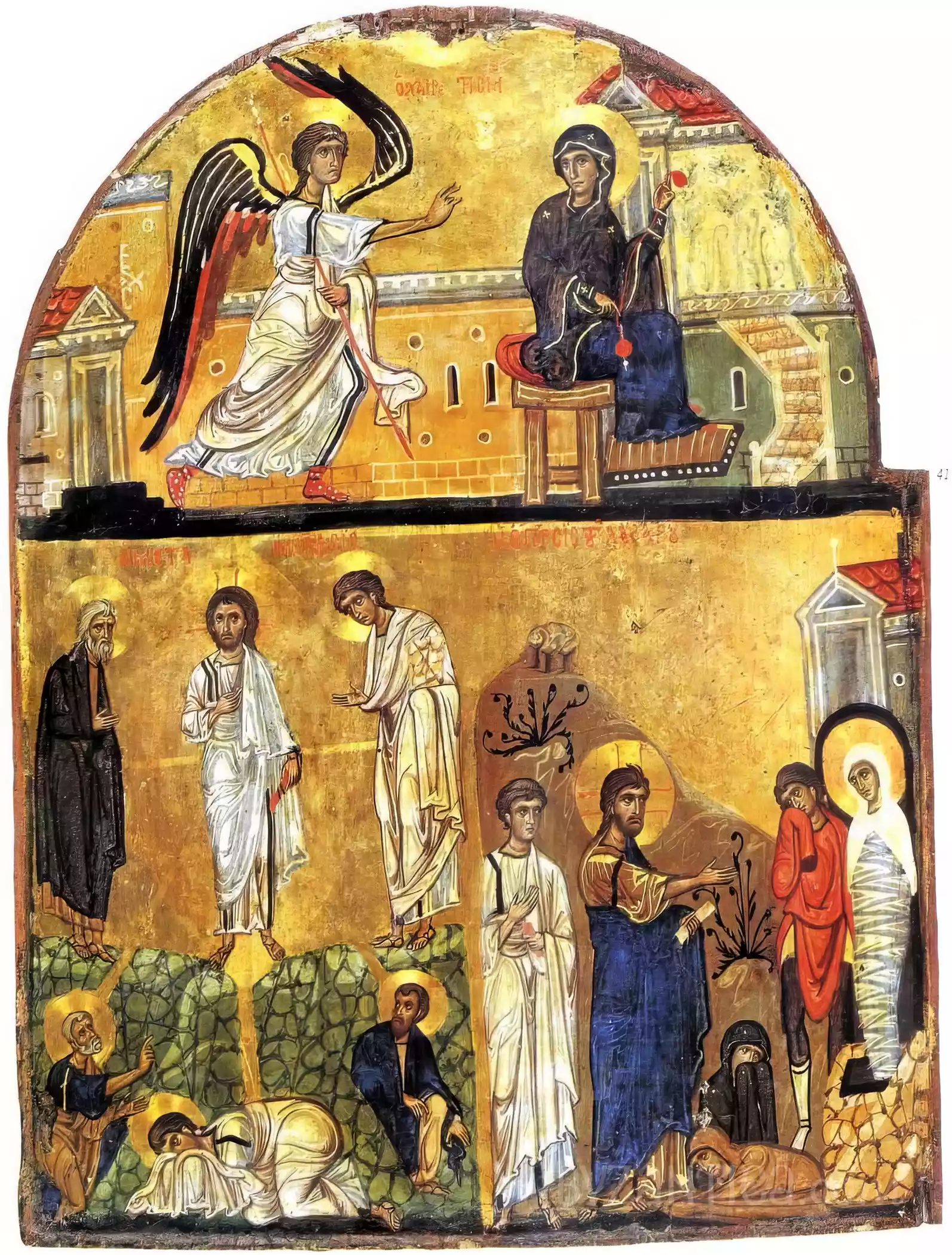

A work of art does not simply constitute an aesthetic proposition; it constitutes primarily a philosophical question that is posed through matter. The Tetraptych of the Dodekaorton, a masterpiece of the late 12th century housed in the Holy Monastery of Saint Catherine in Sinai, constitutes such a case of a visual question. Crafted by an unknown Byzantine virtuoso with tempera and gold leaf upon wood, this work transcends the simple iconographical juxtaposition of sacred scenes. My first contact with this icon did not simply provoke admiration for the technical perfection, but a deeper disquiet about its structural logic, about the silent architecture that governs the relations between its parts. The experience of viewing is transformed into an exercise of interpretation. The golden depth does not function as a simple decorative background, but as a non-place, a space of absolute luminosity that neutralises the usual coordinates of perspective and of time, forcing the gaze to focus on the internal, theological geometry of the composition. The textures, from the cold lustre of the gold to the fluid drapery of the garments and the illusion of porous stone, do not aim for naturalistic mimesis; on the contrary, they constitute a system of symbolic contrasts that invites the viewer to reflect upon the nature of the depicted reality.

The work is structured in two unequal registers, which are separated by a coarse, black horizontal line. In the upper, semi-circular section, the Annunciation of the Theotokos unfolds. In the lower, rectangular, two scenes coexist: the Transfiguration of the Saviour and the Raising of Lazarus. The challenge, therefore, lies not in the recognition of the subjects, but in the investigation of the logic that dictates this specific arrangement. Why this section? Why this coexistence? The question that emerges does not concern so much what is depicted, as how the very structure of the icon — its divisions, its connections, its silences — produces meaning. This tetraptych is not simply a narrative; it is a theological engine that dismembers and recomposes the concept of the Divine Economy, calling into question the linear perception of sacred time.

The Horizontal Section: Logos and History

The most evident and simultaneously the most enigmatic decision of the artist is the strict horizontal division of the surface. The black line is not simply a frame; it is a section, a caesura with profound metaphysical significance. It separates two ontological states. In the upper part, the Annunciation does not simply represent a historical event, but the moment of the Incarnation itself — the invasion of the timeless Logos into history. The Archangel Gabriel, with his unnaturally black wings tearing through the golden light, does not simply offer a lily; he conveys a divine condition that overturns the laws of the world. The Theotokos, seated on an architecturally paradoxical throne, receives the message not as a passive recipient, but as the place where the eternal meets the temporal. This scene is the threshold, the zero point of Christian history.

Below this section, in the rectangular field of history, the incarnate Logos acts. The Transfiguration and the Raising of Lazarus are not simply miracles; they are acts that reveal the dual nature of Christ and prefigure the final meaning of his presence in the world. While the Annunciation is the moment of the coupling of God and man, the lower scenes are the revelation of the consequences of this coupling within the field of decay. The horizontal line, consequently, functions as an ontological delineator: it distinguishes the event of the Incarnation as a supra-historical condition from its manifestation within human history. It functions as the boundary between the silent entry of God into time and his ‘speaking’ action within it. It is the line that separates the eternal decision from its historical realisation, being from becoming.

The Vertical Division: Transfiguration and Glory

If the horizontal section distinguishes eternity from history, the silent vertical line that separates the two scenes of the lower register introduces a new dialectic, this time in the interior of the divine action itself. Left, the Transfiguration on Mount Tabor. Right, the Raising of Lazarus in Bethany. The painter places side-by-side two moments that, although distinct in evangelical time, here co-function as the two faces of the same soteriological mystery. As Robin Cormack observes, these works were not simple representations, but active elements that shaped attitudes and beliefs.

In the Transfiguration, Christ reveals his divine glory, the uncreated light that pre-exists the world, to three chosen disciples. His garments, white as the light (Matthew 17:2), radiate a luminosity that does not originate from an external source, but from his very being. It is a moment of revelation of the divinity within humanity, a preemptive vision of the eschatological reality. Nature, time and human perception seem to retreat before this dazzling experience. Directly beside, the scene of the Raising transports us to the kingdom of decay and of death. Lazarus, ‘four days dead’ and wrapped in his shrouds, represents the absolute condition of the human fall. The face of Christ here does not radiate the serene glory of Tabor, but expresses an imperative authority over death. His movement is an act of sovereignty, a command that Hades is forced to obey. Here, the divinity is not revealed as light, but as power that overturns the very law of decay. The juxtaposition is clear: light versus darkness, glory versus decay, the preemptive vision of Paradise versus the victory over Hades. The icon invites us to reflect upon this duality, to wonder how the revelatory experience of Tabor is related to the subversive act in Bethany.

The Unified Land: Overcoming Duality

And yet, at the very moment that the composition establishes this strict dialectical opposition, at the same moment it undermines and transcends it through an intelligent and theologically dense artistic choice. The rocky hill upon which the transfigured Christ stands does not follow the traditional sharp-peaked and stylised rendering of the Byzantine landscape. On the contrary, the ground is rendered with an unusual naturalness, and most importantly, it continues almost unbroken into the right scene, shaping the rocky mass from which the tomb of Lazarus emerges. The ground of the Transfiguration is the very ground of the Resurrection. This unification of the landscape is not an aesthetic arbitrariness; it is the heart of the work’s theological proposition. The artist, in this way, abolishes the very distinction that he had just established. He tells us that the light of Tabor and the authority over death spring from the same divine-human reality, that glory and victory are inextricably linked. The Transfiguration is not simply a vision of the future Kingdom, but the very power that makes the Raising possible. The revelation of the divine nature of Christ is the prerequisite for the abolition of the power of death. Thus, the icon functions on two levels: first it distinguishes and juxtaposes (eternity/history, light/darkness) and then it composes and unifies, revealing the internal unity behind the apparent contradictions. The section is lifted the moment it is recognised.

Epilogue: The Icon as a Silent Liturgy

The Tetraptych of Sinai is not, ultimately, a simple collection of sacred narratives. It is a silent liturgy, a visual treatise on the nature of salvation. Its structural divisions do not simply demarcate the scenes, but define the very conceptual fields of divine action: the transcendence of time, the revelation of glory and the abolition of death. However, the supreme wisdom of the work lies in the final lifting of these distinctions, in the unification of the ground where the Light of the Transfiguration becomes the stone that is rolled away from the tomb of Lazarus.

The work leaves us with a profound reflection. It invites us to see beyond the linear succession of events and to conceive salvation as a single, multi-faceted act that unfolds simultaneously at the threshold of time and in the heart of human history. This icon does not close, but opens the question of the relationship between the visible and the invisible, between revelation and action. It functions as a mirror where the dividing lines of our own world — life and death, time and eternity — are placed under condition, and for a moment, are contemplated united under the eternal light of the golden depth.

Bibliography

- Baboula, Evanthia, and Lesley Jessop. Art and Material Culture in the Byzantine and Islamic Worlds: Studies in Honour of Erica Cruikshank Dodd. Leiden: Brill, 2021. https://books.google.com/books?id=xsAqEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA9&dq=byzantine+icons&hl=el&newbks=1&newbks_redir=1&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi8so32gpyOAxWSLEQIHTB_Hfk4ChDoAXoECAgQAw

- Cormack, Robin. Writing in Gold: Byzantine Society and Its Icons. London: G. Philip, 1985. https://books.google.com/books?id=LsPpAAAAMAAJ&q=byzantine+icons&dq=byzantine+icons&hl=el&newbks=1&newbks_redir=1&printsec=frontcover&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi8so32gpyOAxWSLEQIHTB_Hfk4ChDoAXoECAoQAw

- Kamil, Jill. The Monastery of Saint Catherine in Sinai: History and Guide. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 1991. https://books.google.com/books?id=nZGrBnInneIC&dq=Sinai+monastery&hl=el&newbks=1&newbks_redir=1&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjB8fjhgpyOAxUMMEQIHfdIA60Q6AF6BAgHEAM

- Krause, Karin. Divine Inspiration in Byzantium: Notions of Authenticity in Art and Theology. Leiden: Brill, 2022. https://books.google.com/books?id=aJ59EAAAQBAJ&pg=PT367&dq=byzantine+icons&hl=el&newbks=1&newbks_redir=1&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi6odGLg5yOAxUWKEQIHTzcLSk4FBDoAXoECAsQAw